articles / Science

Bolero, Obsession, and the Brain

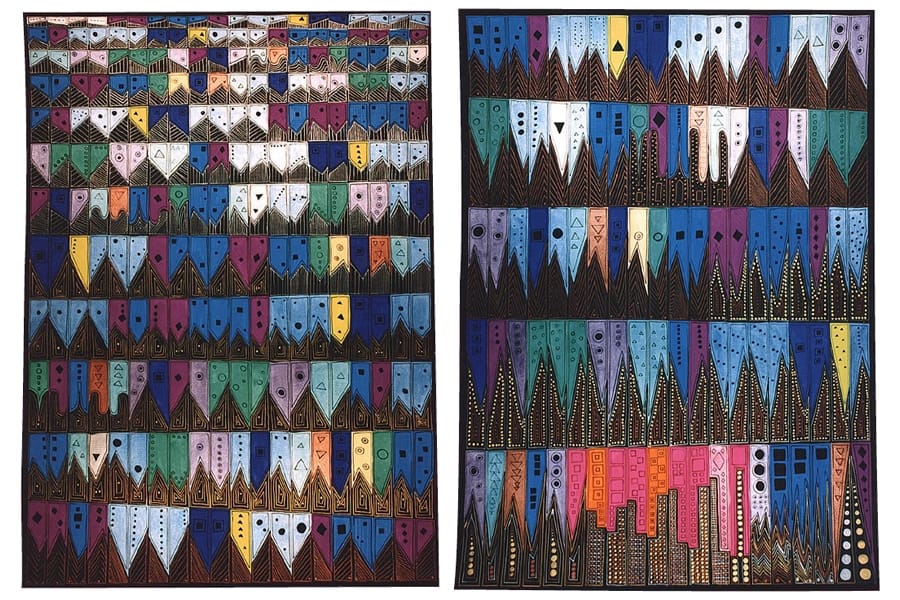

The painting above, Unraveling Bolero shows a precise graphic representation of Ravel’s Bolero… It was painted by Anne Adams, whose life and artwork would be connected to Maurice Ravel in another, tragic way. They both began to experience progressive aphasia toward the end of their lives, which would take away their speech, and influence their creativity. This Monday evening, the San Francisco Conservatory of Music teams with the UCSF Memory and Aging Center and the Global Brain Health Institute to discuss how the arts and brain science can intersect. Among the participants are SFCM President David Stull, and UCSF’s Dr. Bruce Miller.

The event is sold out (although there is a wait list here) – to find out more about the story, you can listen this edition of WNYC’s Radiolab.

The obsessiveness with which Adams detailed her painting actually was one of the signals that this kind of dementia was starting to set in – which also explains Ravel’s work itself. When Anne Adams began having trouble with words, they looked at scans of her brain that had been taken earlier, and compared them to more recent ones. “Around the time that she produced this magnificent painting, her brain was quite a bit larger statistically in the right posterior cortex, and her language area was profoundly diminished in size,” Dr. Bruce Miller says. “We realized that this new curiosity about painting, this new painting that she had undertaken, was occurring in the setting of a slow progressive loss of structure in her language region.” That she should direct her artistic focus onto a work by a composer with the same ultimate diagnosis helped move both science and art forward. David Stull, president of SFCM, says the symposium next Monday evening came about after they realized there was a significant overlap of interests with the GBHI. “We were discussing music, and its relation to neuroscience, and in particular its relationship to not only cognitive development, but also what we know about decline. The research UCSF is focusing on often includes music… We felt that both schools could really learn from one another, and that there was a real public interest here in discovering how music plays such a critical role in our lives, and also how it informs, scientifically, our understanding of both brain development and brain decline.”