If you’ve been to an SF Symphony performance at Davies Symphony Hall in the last 17 years, there’s a good chance you would have heard concertmaster Alexander Barantschik playing a masterpiece of musical history.

It is called “The David“– a 1742 Guarneri Violin, and it was present at the creation of one of the world’s most beloved compositions for that instrument, Felix Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto in E minor.

This wonder of a musical instrument is on permanent loan to Barantschik, who uses it only for his hometown performances. For a few more weeks, the Guarneri is on view to the public at SF’s Legion of Honor Museum, through August 10th.

Giuseppe Antonio Guarneri (and Antonio Stradivari), working in Cremona, Italy in the 17th and 18th centuries, created instruments whose sound is unrivaled by violin makers to this day. The mystery of their distinct sound remains unsolved, though there are plenty of theories: perhaps it was the 200-year-old wood from Lebanese Spruce trees, maybe the wood was thicker due to a cooler climate, maybe it was the varnish, maybe it’s magic.

A Guarneri violin, once owned by Niccolò Paganini

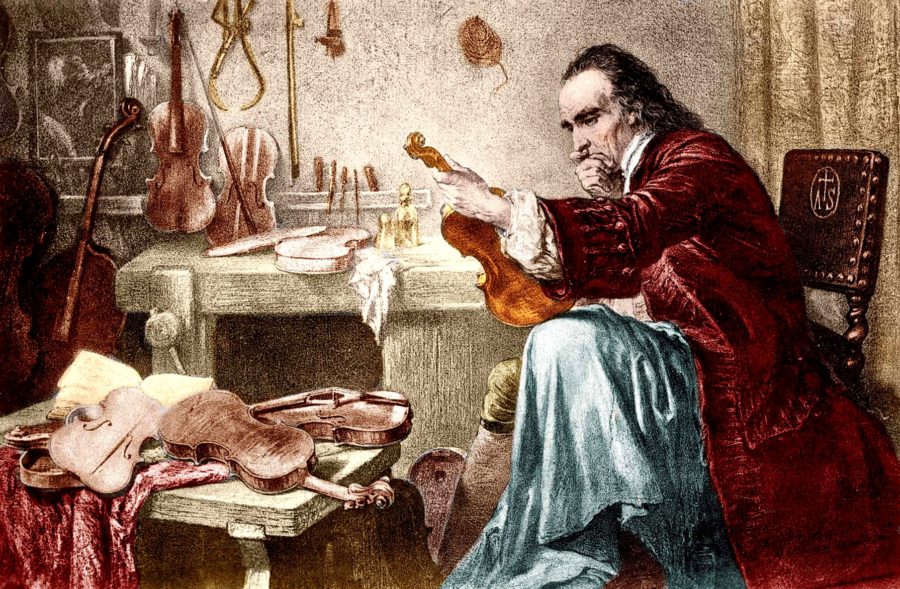

Antonio Stradivari examining his work

Violin making was a family business for the Guarneris, but it wasn’t until the early 19th century that their instruments found their way out of Italy, and into the hands of musicians who prized them above all others. One of those musicians was Ferdinand David, the virtuosic concertmaster of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, who advised Mendelssohn in writing his great violin concerto. In 1845, David gave the premier of that concerto with the Guarneri that now bears his name.

“There are many violinists, and then there is Heifetz” – Russian violinist David Oistrakh

Fast forward to 1922, when the Russian-American violinist Jascha Heifetz, who wowed the musical world at age 11 with his first public performance of the Mendelssohn concerto, purchased the very instrument that birthed that piece.

In his day, Heifetz was considered the greatest violinist of the 20th century. After hearing that first concert, Fritz Kreisler said, “Well gentlemen, we might as well all break our violins across our knees!

Heifetz and family immigrated to San Francisco in 1917, made his debut at Carnegie Hall that same year, and remained the “Violinist of the Century” throughout his life. He played the Guarneri for almost all of his concerts and recordings.

When Heifetz died in 1987, he bequeathed his favorite instrument to the SF Fine Arts Museums with the stipulation that it be played on special occasions by worthy performers such as Isaac Stern, Itzhak Perlman, and Gil Shaham. But, realizing that such an instrument must be played to remain vital, in 2002, the museum made the deal to offer “The David” on permanent loan to Alexander Barantschik.

When he first took possession on the violin, Barantchick says, “it was sleeping and needed to be woken up”. He calls it a lifetime relationship “it is very much alive [with]…good days and bad days.” The violin’s “big, rich sound” is made to dominate. As a soloist in front of an orchestra, Barantchik says he can play at full volume, or very softly, and he knows he will be heard at the back of the hall.

The history and parallels of “The David” continue to resonate. Jasha Heifetz has always been an idol of Alexander Barantchik. When he was a student at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, his lessons were in the same room where Heifetz studied. His portrait was on the wall in the room “staring me in the face while I practiced and learned.”

Barantschik says he “didn’t know this violin was in San Francisco until I came here. Life is so unpredictable! If someone had told me then, back in Saint Petersburg, that I would one day be playing Heifetz’s violin, I would have died on the spot.”